by RNS | Nov 12, 2020 | Beating Tsundoku

Ioulia Kolovou, Anna Komnene and the Alexiad (Pen & Sword, 2020)

If you think you know Anna Komnene, the 12th Century Byzantine princess, as a ruthless and ambitious shrew who plotted to kill her brother and take the throne, then Ioulia Kolovou is here to put you straight. Anna was none of those things. She was a pioneering intellectual, opinionated, strong in character, and a victim of historical misunderstanding and misogyny.

Kolovou sets the scene with the cast of characters inhabiting the opulence of mediaeval Byzantium. Anna Komnene sits in a nunnery in 1147, writing a eulogy to her father, Alexios I Komnenos, called The Alexiad. Kolovou uses that piece of historical fiction to introduce Anna, her history, and its impact on future historians. Kolovou draws back to narrate the rise of the Komnenoi family in Byzantium. It wasn’t pretty, but in his ascendancy Alexios I Komnenos married and united two great families and secured the throne. Anna’s birth consolidated the dynastic marriage. Kolovou follows Anna as she grew up in Byzantium; her family life in the Imperial palace; her betrothal and moving in with her intended in-laws at 7; her return at 12 after all that fell apart; and her education. Then came marriage to a suitable, beautiful, noble match, when she was 14. Her husband, Nikephoros Bryennios, encouraged Anna’s studies, and she was a brilliant student. She also had children, and Kolovou highlights that it is easier to recover Anna’s boys than her girls in the historical record. With that Kolovou takes us on a tour of the Imperial family and the nature of power in Byzantium.

In 1118, Alexios died, setting off a power struggle that Kolovou presents through the various sources, concluding with a discussion of Anna’s role in it against her brother. Kolovou moves on to Anna writing the Alexiad in the nunnery. She takes great pains to point out that Anna was not forced into the convent, or that she lived out her life as a nun; this was just her new home. With her husband’s death in 1138, Anna was free to pursue her intellectual life and writing her famous history. Kolovou analyses Anna’s take on the First Crusade in a lengthy exegesis for what is a relatively short biography. That precedes her account of Anna’s death as a proper nun in 1153 and a discussion of her legacy. Kolovou tidies up her biography with appendices of maps, genealogy, and chronology.

Kolovou’s hope for her biography of Anna Komnene is that you will read The Alexiad with a new understanding of the woman who wrote it. She therefore writes in a looser style for public consumption rather than for academic scrutiny, but still with authority. Kolovou succeeds in penetrating the elite Byzantine world and making it accessible, which is no mean feat. She also rescues Anna from the talons of misogynist historians and places her where she belongs as an extraordinary, but very human, woman, not the monster we have been led to expect. In doing so, Kolovou has performed a useful service to Anna Komnene and history.

BUY NOW

by RNS | Nov 10, 2020 | Beating Tsundoku

António Barrento, Guerra Fantástica The Portuguese Army in the Seven Years War (Helion, 2020)

In this slim but informative monograph, António Barrento narrates a most peculiar war between Portugal and Spain in 1762. In doing so, he brings what is usually considered a mere sideshow of the major war going on elsewhere in Europe onto a bigger stage.

Barrento begins with a repetitious introduction that should have been strangled in the draft stage, but the book picks up after that with a brief but useful overview of Europe in the mid-Eighteenth Century. He follows that with a description of warfare and the use of military force, ending in a synopsis of the Seven Years War. Most of us are familiar with the major players in that War – Britain, France, Russia, Prussia, and Austria – but my guess is that Spain and Portugal probably do not make that list. Barrento describes the Portuguese army in the years before the War in Europe as ‘nominal’ and in need of a rapid overhaul. Tensions with Spain and France added to the sense of urgency. An ultimatum was issued to Portugal in March 1762 for the Portuguese to break with the British, which they refused, promising to defend Portugal’s borders. If only they had an army to do that. Barrento dismantles what little army the Portuguese did have, which was not much particularly compared to the Franco-Spanish army on the eve of their invasion on 24 February 1762. In the end, despite some successes, the Spanish first effort met greater than expected resistance from irregular forces. In the meantime, British forces arrived to bolster the Portuguese, but the initiative remained with the Spanish. Yet local opposition, disease, desertion, and effective Anglo-Portuguese manoeuvring under the command of the excellent Count of Lippe, wore down the Spanish, forcing them to retreat and ultimately seek peace. The war was over by the end of November 1762.

For the most part, Barrento tells an interesting tale of strategic marches and counter-marches with the Spanish implementing a seemingly confused war plan and the Anglo-Portuguese stymying them at just about every turn. His narrative of operations effectively untangles the flow of events, revealing a much more serious affair than is sometimes accredited elsewhere in the history books. He is ably supported by Helion’s usual high quality illustrations of soldiers and contemporary prints and maps. Barrento’s rather polemical conclusion, however, based on a 250 years old lesson, puts a puzzling cap on his otherwise balanced account of a significant moment in Portugal’s history. Eighteenth Century warfare enthusiasts will enjoy this book as will anyone interested in the Iberian Peninsula’s history of long running conflicts.

BUY NOW

by RNS | Nov 8, 2020 | Beating Tsundoku

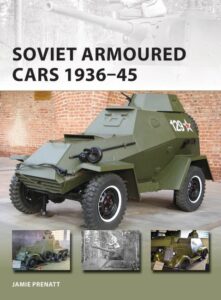

Jamie Prenatt, Soviet Armoured Cars 1936-45 (Osprey, 2020)

In this slim volume in Osprey’s New Vanguard series, Jamie Prenatt surveys a weapon not usually associated with Soviet armies: the armoured car. It is perhaps more surprising that they had been in Russian service since before the 1917 Revolution and during the Russian Civil War.

The first Red Army mechanized brigade was formed in 1929, consisting of 17 armoured cars, and a deal with Ford (!) the same year boosted design and production. Soviet armoured vehicles were heavy when equipped with cannons and light if armed only with machine guns. And with that, Prenatt works his way through the various models assisted by black and white photographs and colour illustrations. He follows up with an overview of Soviet armoured cars in action, including the Spanish Civil War, the Khalkin Gol campaign in Mongolia, the Invasion of Poland, the Winter War, and, of course, World War II. The final batch of World War II Armoured cars continued in service until the 1950s.

Soviet Armoured Cars 1936-45 is a neat and tidy little book on a weapon that proved effective in the right tactical circumstances. Prenatt does not get too bogged down in the technical details and his narrative accounts of the vehicles in action are basic but informative. All in all, this is a useful addition to the series.

BUY NOW

by RNS | Nov 7, 2020 | Beating Tsundoku

Robert C Stern, The Modern Cruiser (Seaforth Publishing, 2020)

In warship designations, what is, or rather was, a Cruiser? Robert Stern is here to tell you, though he too finds them hard to define because there was no one size fits all ship for that classification. Stern’s narrative survey follows the full cycle of the Cruiser’s operational life from the 19th to the 21st Century in a lavishly illustrated, coffee-table sized book that is a must for modern naval history enthusiasts.

Cruisers came from those ships in the 19th Century that performed tasks not assigned to ships of the line. In the later 19th Century, there were three classes of Cruiser based on size. They retained their masts but were iron-hulled and coal-powered. Steel replaced iron and sailing rigs were discarded as they were built for speed and firepower. These Protected Cruisers met in battle during the First Sino-Japanese War at the Yalu River in 1894. A watershed in Cruiser design with two new types, including the light Cruiser, took place in 1897. This generation of Cruisers started to look like modern Cruisers with turret guns and a more elegant streamlined design. But could they fight? World War I would test them as they chased each other all over the oceans. Stern expertly describes the subsequent engagements, including the Battles of Coronel, the Falklands, and of course Jutland. Of all the different Cruiser types, only the light Cruiser emerged with its reputation intact into the 1920s where further developments awaited. Stern describes how the Washington Treaty affected that through its limitation of Capital shipbuilding. Cruisers now had a maximum size, which meant putting as much as possible on them; a designer’s nightmare. Nevertheless. Cruiser construction accelerated, requiring two further treaties to try and slow production, but by the mid-1930s those efforts had been abandoned. By then the Germans were ignoring the rules anyway and a Cruiser arms race followed. That would continue into World War II. Stern examines Cruiser performance in three engagements in that war, including Savo Island in 1942. Cruisers became an anachronism in the post-war world but not immediately. They were transformed into guided-missile Cruisers though some kept their guns. Stern concludes that there is still a role for Cruisers, but sadly none are still afloat.

The Modern Cruiser is a very detailed book covering every aspect of those vessels from drawing board to combat performance. Stern examines individual ships and classes throughout, highlighting improvements but also their problems. The result is a real sense of evolution, befitting the book’s subtitle. Stern’s discussion of the politics of Cruiser building is well-balanced and informative, particularly the chapters on between-the-wars initiatives. A superb collection of photographs illustrates Stern’s thoroughly researched and well-written book. Anyone interested in 20th Century warships will enjoy this book.

BUY NOW

by RNS | Nov 2, 2020 | Beating Tsundoku

Ben Macintyre, Agent Sonya (Viking Books, 2020)

Oxfordshire, England, late 1940s. There is a lady lives in your village; a Women’s Guild type but keeps herself to herself. She loves her children, a doting mother even. She goes for long rides into the countryside on her bicycle, sometimes for hours. No one in the village is quite sure what she does for her money, though she rarely appears short. Then one day, she disappears without a word to anyone. You find out later that the woman in your midst was a spy for the Soviet Union named Ursula Kuczynski. It’s a scenario straight out of a Le Carre novel, but it was true. In Agent Sonya, Ben Macintyre narrates the extraordinary life of this redoubtable spy.

Kuczynski grew up in a middle-class Jewish German family, her father a prominent left-wing economist. This was not the background of a specialist spy, but Kuczynski had an independent streak and came of age during the rise of fascism. She drifted into communism, an ideology she never eschewed despite some severe tests. Kuczynski travelled to the USA, came home and married, then moved to China in 1930 and had a child. She was recruited as a Soviet agent by master-spy Richard Sorge who gave her the codename Sonya. The Soviets trained her as a radio operator then sent her back to China with another man. She had a child by him too, but while she loved her children that did not interfere with Kuczynski’s espionage. She was recalled to Russia in 1935 then transferred to Poland. Her husband stayed behind in China.

Switzerland was Kuczynski’s next stop where she ran agents into Germany. She divorced her first husband and married a fellow agent who was British. Kuczynski came to England in 1943, as Ruth Werner, moving around before settling in Great Rollright in Oxfordshire. As with everywhere else, she set up an illegal radio in her new house and began transmitting to Moscow. She and another spy infiltrated the American OSS, having double-agents sent to Germany. Kuczynski is most famous for handling the atomic spy Klaus Fuchs whose secrets she sent to Moscow, putting them in the atomic bomb race. She was ineptly interviewed twice by MI5, but when they caught Fuchs the game was up for Kuczynski. She fled England for Berlin on the eve of Fuchs’ trial and before he gave her up. She worked in the new GDR and authored several children’s books and her memoir. Kuczynski died in 2000 her communist beliefs intact.

Ben Macintyre should need no introduction; he is surely the leading writer of spy stories in England. With a Macintyre book, you get a fast-paced, tightly-knit story that reads like a novel. Agent Sonya is no different. Macintyre has a telling eye for detail that breathes life into his characters without becoming bogged down in minutiae, and his sense of the dramatic enlivens the text. Do not be lulled, however, into thinking that Macintyre is anything other than a thorough historian who does his research as his endnotes and bibliography attest. As for Ursula Kuczynski, she lived a charmed life, but she also made her own luck through her skill and fortitude. She was cunning, charming, diligent, and disarming; everything you need in a spy. Macintyre captures all of that expertly, and anyone interested in espionage will enjoy this book.

BUY NOW